Cloak and Dagger

Angela Fette, Sascha Hahn, Alice Könitz, Sonia Morange, Julia Oschatz, Jemima Wyman

October 1—November 4, 2018

Co-organized with Commonwealth & Council

Chapman University’s Guggenheim Gallery, Orange, CA

Cloak and Dagger gathers a selection of masks, costumes, paintings, and videos by six American and German artists. Through vastly divergent uses of masking and cloaking strategies, they manifest new agencies at the vanguard of ideological inquiry and self-presentation.

Undercover agents gain access to secrets, disguised assailants attack unnoticed, a masked shaman communes with the supernatural, while many colonized subjects bear the internal “white masks” of servile psychology and shame. Both deceiving and not, masks present many appearances, meant to tell friend from foe, provide anonymity, or invoke spirits, gods, and others. Whether concealing or revealing identity, posing a decoy, masquerade, or symbolic ritual face, masking and unmasking enacts a powerful double vision—a ritual process that brings everyday reality into complex relation with the hidden, illicit, abstract, and sublime.

The ancient Roman sense of persona—which literally translates to mask, while also describing someone with full citizenship—shows the paradoxical root of a word that for us describes individuality in a complete sense: personality is understood to be the highest order of self-expression. And yet the origins of the word betray a more nuanced provisionality at work—where a "person" may ultimately be thought to function as a kind of signal relay within a networked order of references, switching personae to suit. This Janus-headed quality underlies both self fashioning and presentation; personality is built up through masking, which conceals individuality while proliferating options for reconfiguring one's identity in the collective imagination.

The abstraction and formalization of selfhood reaches back into early childhood, beyond the constraints of social reality. The fertile playground of the child's mind persists into adulthood and at a deeper level, it shows our second face. This face is the one we put on to communicate to the other side: the other within us. Our animate self exists not here but there—in some exceptional realm, separate from ordinary experience and invoked perhaps through ritual—which crucially binds our sense of the world.

A Matter of Course

Jedediah Caesar, Whit Deschner, Cara Despain, Paul Harris, Haley Hopkins, Virginia Katz, John Knuth, Candice Lin, Tony Marsh, Alison Pirie, Cole Sternberg, Richard Turner, Viewing stones from the collection of Thomas S. Elias and Hiromi Nakoji

Co-curated with Richard Turner

August 13 – September 23, 2018

Chapman University’s Guggenheim Gallery, Orange, CA

A Matter Of Course; Catalog

A Matter of Course pairs viewing stones with works of fine art. Viewing stones is an umbrella term for stones that are collected and displayed for aesthetic purposes. Chinese stones are commonly called Scholar's Rocks. Japanese stones are known as Suiseki. The viewing stones in this exhibition, which are from the collection of Thomas S. Elias and Hiromi Nakoji, are representative of the various forces that have shaped them – water, wind, heat, pressure, and human hands.

The artworks in the exhibition are by artists whose creative process shares agency with non-human forces in a multiplicity of ways. They interrogate the arguable distinction between humankind and the ecosystems in which we co-exist.

Oregon rancher Whit Deschner shows a salt lick shaped by the tongues of his neighbors’ cattle. John Knuth uses 45,000 houseflies which he feeds a mixture of sugar water and acrylic paint, to produce his (neo-) pointillistic paintings. Cole Sternberg engages the power of the waves to scrub his canvasses as he drags them through the water behind a power boat. Virginia Katz collaborates with the wind to generate the dense linear meshes that comprise her drawings. Tony Marsh’s ceramic vessels are the result of the unpredictable alchemy of the kiln, which Marsh embraces wholeheartedly rather than trying to control its results. Richard Turner’s drawings, which he produces by rolling ink and paint-covered river rocks back and forth over cold-press paper hundreds of times, oscillate between human and non-human agency. Candice Lin’s Putrefaction installation includes live koji mold as part of her rumination on the decay of the human body. Paul Harris’ sculptures pair stone and wood in intimate embrace. Cara Despain’s concrete casts of rocks invite us to travel to the Utah desert to experience the stones in situ. Jedediah Caesar’s piece appears to be a mineral specimen but in fact is a sculpture fashioned from resin, stones and an emu egg. Haley Hopkins’ and Alison Piries’ collaborative video installation presents the hypnotic movements of snails and contrasts it to our own motions in space. A catalogue with essays by Richard Turner, Thomas S. Elias and Kylie White accompanies the exhibition and will be available at the September 16, 2018 reception.

Genius Loci 6 Focus Los Angeles: Present Progressive

Michael Dopp, Mark Flores, Pearl Hsiung, Pamela Jordan, Raffi Kalendarian, Michael John Kelly, Rachel LaBine, Emily Marchand, John Mills

July 5 – August 24, 2018

Setareh Gallery, Duesseldorf, Germany

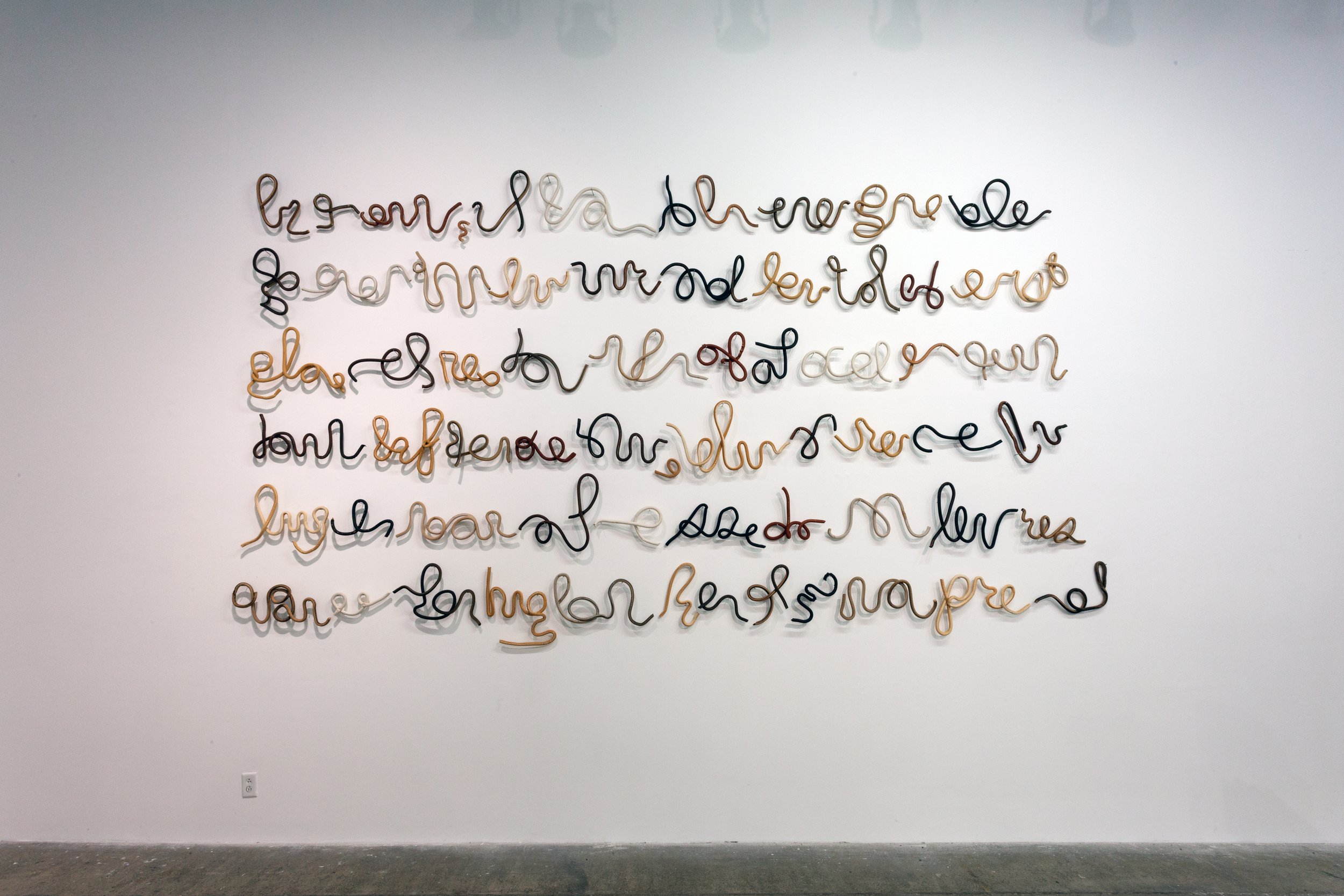

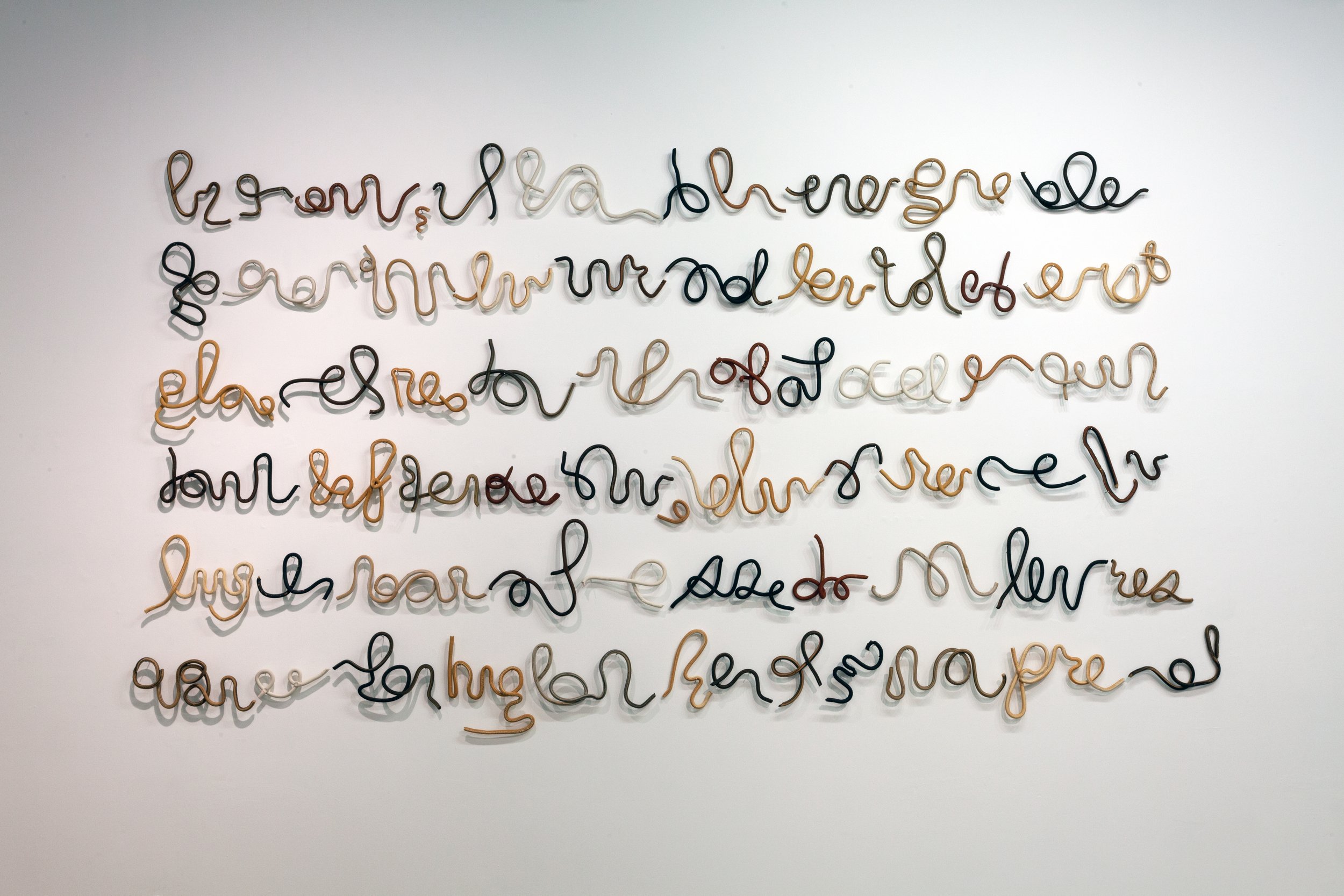

Glass Tambourine

Mark Flores, Gregor Gleiwitz, Pearl Hsiung, Pamela Jordan, Michael John Kelly, Rachel LaBine, Emily Marchand

January 29th – March 11th, 2018

Chapman University’s Guggenheim Gallery, Orange, CA

Is space a form of enlightenment?

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

A glass tambourine is certainly difficult to use. It would be interesting to know what kind of frequencies you actually produce when you play it, provided it does not break. On the one hand, it offers the advantage of being absolutely clear, so to speak, transparent. On the other, it has been understood, seen through, and is now an object without any secret. The inclined reader already suspects that the exhibition title is not meant in a literal or poetic way, but rather figuratively alludes to a certain condition, namely the availability of forms of expression that are decontextualized from their origin into an empty form.

An example of this inner emptiness is the tambourine-sound imitated in the computer with the help of emulated synthesizers, or the plethora of visual effects that we have at our disposal in digital photo- and video-editing. They aim to deliver a specific sound or look that has been decided in advance, disassembled into its parts and analyzed, put back together and readily available for purchase and use. But the idea that the computer is a toolbox with which the artist now accesses a world of boundless expression is erroneous because the box itself is the only tool we work with. The use of once vital forms of artistic expression that are now applied out of context to produce a certain effect we could call kitsch - the opposite of avant-garde. A Taoist would probably add that when the outcome of an action is known with certainty, this action is already in the past. Whatever we call it, in it we recognize the same worldview that determines our global economy, our political landscape and 'social’ media. And we see it transposed into the realm of art, which, in the sense of a continued modernist utopia, whether it be ‘post’ or otherwise altered, represents the exact opposite of the precisely quantified and standardized product. And so we find flocks of artists far from their actual mission, the discovery of visionary and surprising expressions, now merely working in so-called industries to re-arrange prefabricated components.

Are now the artists in the exhibition examples and illustrations of the opposite state? And what is this state? Should I throw away my computer? Maybe after I’m finished typing this text. We can’t turn back the digital clocks nor do we want to and lines are hard to draw; Standardization begins long before I switch on my computer with the use of industrially produced paints, brushes, canvases. Then cameras, monitors, etc.

The works the artists in the exhibition create however are arrived at in dialogue with the used materials, which is informed by a kind of behavior that is directed towards this material, acknowledging its existence as much as ones own. We, our bodies, do this in space. This processual ‘acting-in-accordance-with’ lets us be active participants, wholly present in the unfolding of the becoming of the artwork. This goes beyond the production of a predicted effect and hints at the possibilities of something unfolding, a development over time, and the notion of surprise as positive values, whereas in the currently dominating view these qualities are seen as obstacles to be overcome or eradicated. Think: (Profit) maximization, streamlining and efficiency, terms that are increasingly also describing forms of contemporary art practice. We can infinitely access and manipulate the recordings of past forms of expression to our liking in a kind of master/slave relation - but we are also fundamentally separated from the world in that we exclude our corporeality and its entanglement with the environment and all the reverberations this can have in our art.

For the artists in the exhibition, what is 'said' is inevitably associated with its own physicality. This goes beyond the notion of the integration of form and content, but rather requires that expression and form create and suppose one another. Creative process takes place in an open interactive loop as a negotiation of material, and its formability, and the artist and their formability. The works in the show all have a heightened awareness for a body that does not only see with its eyes; be it the stacked and boxed painting-sculptures by Mark Flores, abstract clay handwritings by Emily Marchand, Pearl C. Hsiung’s neon-landscape installation, Gregor Gleiwitz’s ectoplasmatic beings, the virtual line drawings in space by Michael John Kelley, paintings by Pam Jorden that juxtapose geometry with painterly geography, or the precise gestural formulations of thingness in Rachel LaBine’s works.

And so the exhibition asks: What is different when we play a tambourine that is made of wood and skin and metal? The sound?